Post

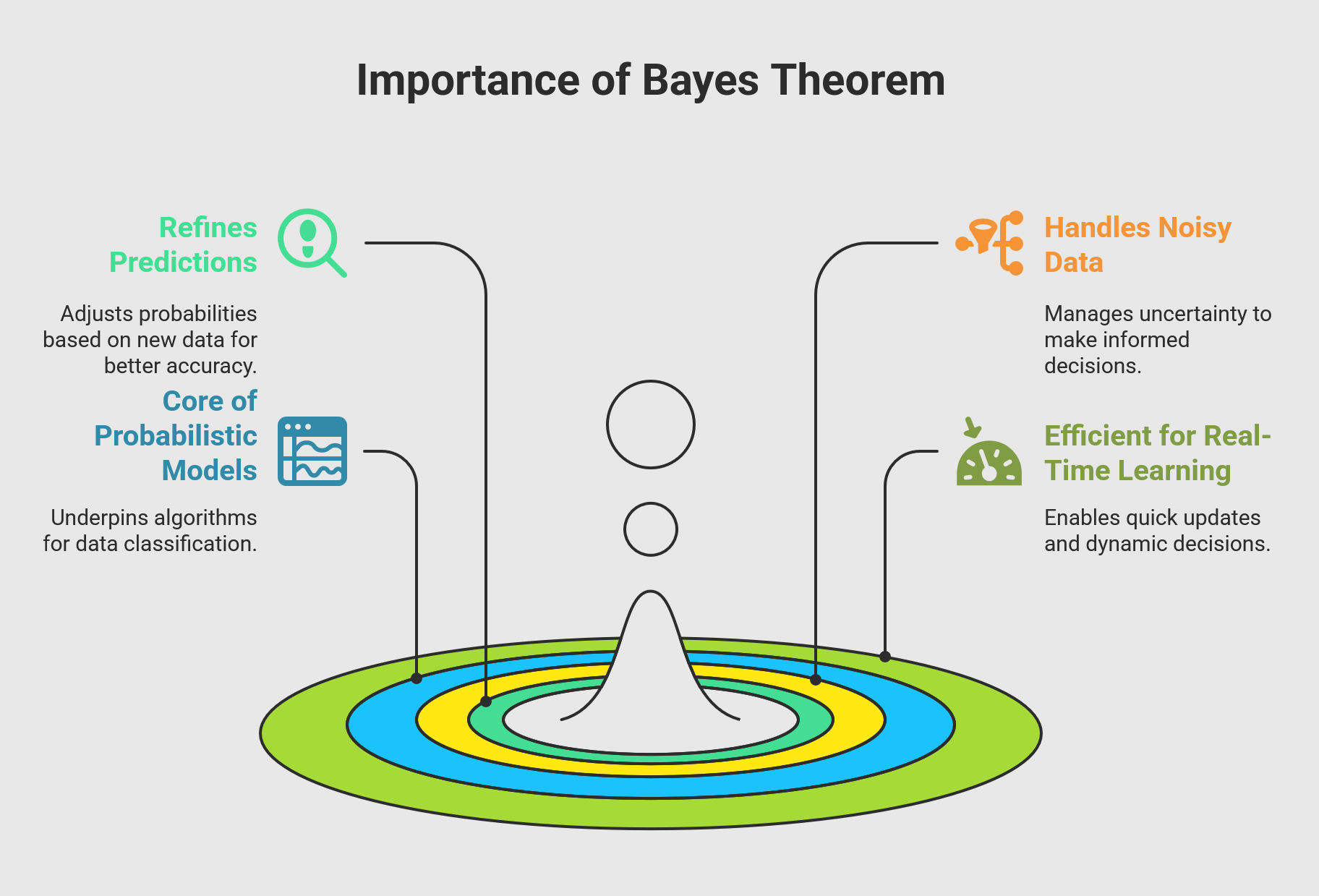

What is Bayes’ Theorem?

Bayes' Theorem is a way of finding a probability when we know certain other probabilities.

Suppose a patient goes to see their doctor. The doctor performs a test with 99 percent reliability— that is, 99% of people who are sick test positive and 99% of healthy people test negative. The doctor knows that only 1% of the people in the country are sick. Now the question is: if the patient tests positive, what are the chances the patient is sick?

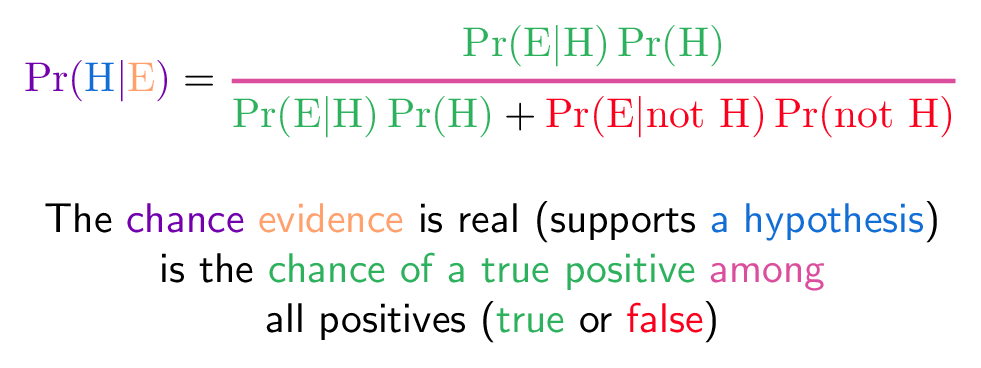

The intuitive answer is 99 percent, but the correct answer is 50 percent. Bayes provides us a

framework to understand why. He stated the defining relationship expressing the probability you test positive

AND are sick as the product of the likelihood that you test positive GIVEN that you are sick and the "prior"

probability that you are sick. Said another way, the probability the patient is sick, prior to specifying a

particular patient and administering the test. Bayes's theorem defines the relationship between what we

know and what we want to know in this problem. What we are given (what we know) is

p(+|s), which a mathematician would read as "the probability of testing positive given that you

are sick". What we want to know is p(s|+), or "the probability of being sick given that

you tested positive."

Rather than relying on Bayes's math to help us with this, let's consider another example. Imagine that the

above story takes place in a small city, with 10,000 people. From the prior p(s)=0.01, we know that

1 percent, or 100 people, are sick, and 9,900 are healthy. If we administer the test to everyone, the most

probable result is that 99 of the 100 sick people test positive. Since the test has a 1 percent error rate,

however, it is also probable that 99 of the healthy people test positive. Now if the doctor

sends everyone who tests positive to the hospital, there will be an equal number of healthy and sick patients.

If you meet one, even though you are armed with the information that the patient tested positive, there is only

a 50 percent chance this person is actually sick.

-

Tests are not the event. We have a cancer test, separate from the event of actually having cancer. We have a test for spam, separate from the event of actually having a spam message.

Now imagine the doctor moves to another country, performing the same test, with the same likelihood

(p(+|s)), and, for that matter, the same success rate for healthy people, which we might call

p(-|h), "the probability of scoring negative given that one is healthy." In our example

city, however, we suppose that only one in every 200 people is sick. If a new patient tests positive, it is

actually more probable that the patient is healthy than sick. The doctor needs to update the prior.

What is the probability of the existence of God? What scientific value does it have?

Scientific analysis of religion is always a popular topic. In Richard Dawkins's book, The God Delusion, he argues specifically against the use of Bayes's theorem for assigning a probability to God's existence. Arguments employing Bayes's theorem calculate the probability of God given our experiences in the world (the existence of evil, religious experiences, etc.) and assign numbers to the likelihood of these facts given existence or nonexistence of God, as well as to the prior belief of God's existence--the probability we would assign to the existence of God if we had no data from our experiences. Dawkins's argument is not with the veracity of Bayes's theorem itself, whose proof is direct and unassailable, but rather with the lack of data to put into this formula by those employing it to argue for the existence of God. The equation is perfectly accurate, but the numbers inserted are, to quote Dawkins, "not measured quantities but personal judgments, turned into numbers for the sake of the exercise."

This is mildly salacious but hardly novel. Richard Swinburne, for example, a philosopher of science turned philosopher of religion (and Dawkins's colleague at Oxford), estimated the probability of God's existence to be more than 50 percent in 1979 and, in 2003, calculated the probability of the resurrection [presumably of both Jesus and his followers] to be "something like 97 percent." (Swinburne assigns God a prior probability of 50 percent since there are only two choices: God exists or does not. Dawkins, on the other hand, believes "there's an infinite number of things that some people at one time or another have believed in ... God, Flying Spaghetti Monster, fairies, or whatever," which would correspondingly lower each outcome's prior probability.) In reviewing the history of Bayes's theorem and theology, one might wonder what Reverend Bayes had to say about this, and whether Bayes introduced his theorem as part of a similar argument for the existence of God. But the good reverend said nothing on the subject, and his theorem was introduced posthumously as part of his solution to predicting the probability of an event given specific conditions. In fact, while there is plenty of material on lotteries and hyperbolic logarithms, there is no mention of God in Bayes's "Essay towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances," presented after his death to the Royal Society of London in 1763 (read it here).

One primary scientific value of Bayes's theorem today is in comparing models to data and selecting the best

model given those data. For example, imagine two mathematical models, A and B, from which one can calculate the

likelihood of any data given the model (p(D|A) and p(D|B)). For example, model A might

be one in which spacetime is 11-dimensional, and model B one in which spacetime is 26-dimensional. Once I have

performed a quantitative measurement and obtained some data D, one needs to calculate the relative probability

of the two models: p(A|D)/p(B|D). Note that just as in relating p(+|s) to

p(s|+), I can equate this relative probability to p(D|A)p(A)/p(D|B)p(B). To some, this

relationship is the source of deep joy; to others, maddening frustration.

The source of this frustration is the unknown priors, p(A) and p(B). What does it

mean to have prior belief about the probability of a mathematical model? Answering this question opens up a

bitter internecine can of worms between "the Bayesians" and "the frequentists," a mathematical gang war which

I'll steer clear of here. To oversimplify, "Bayesian probability" is an interpretation of probability as the

degree of belief in a hypothesis; "frequentist probability is an interpretation of probability as the frequency

of a particular outcome in a large number of experimental trials. In the case of our original doctor, estimating

the prior can mean the difference between more-than-likely and less-than-likely prognosis. In the case of model

selection, particularly when two disputants have strong prior beliefs that are diametrically opposed (belief

versus nonbelief), Bayes's theorem can lead to more conflict than clarity.

Blue Cab Hit and Run

Another practical example of using Bayes' Theorem comes from Daniel Kahneman's book, Thinking Fast and Slow.

A cab was involved in a hit and run accident at night. Two cab companies, the Green and the Blue, operate in the city. 85% of the cabs in the city are Green and 15% are Blue. A witness identified the cab as Blue. The court tested the reliability of the witness under the same circumstances that existed on the night of the accident and concluded that the witness correctly identified each one of the two colours 80% of the time and failed 20% of the time. What is the probability that the cab involved in the accident was Blue rather than Green knowing that this witness identified it as Blue?

How it Works

- The base rate (Bayesian prior) probability is 0.15 because 15% of the cars are blue.

- The hit rate is 0.80 because the reliability of the witness is 80% correct identification.

- The false alarm rate is 0.20 because the witness is incorrect 20% of the time.

-

Bayes formula:

(x*y) / (x*y) + (z*1 - z*x)

x = base rate

y = hit rate

z = false alarm rate

If we plug the base rate for the blue cabs (15%), 80% hit rate and 20% miss rate, we see the probability the hit

and run cab was blue is only 41%. Thus, Even though the witness is correct 80% of the time the actually

probability the cab was blue is 41%. The theorem results are most influenced and weighted by the base rate

(prior probability). The result is more likely to be near the base rate. This is true even if an evidence event

seems to be high proof of the hypothesis. A base rate of 1% will result in 3.88% probability of hypothesis with

a hit rate at 80%. If a base rate probability is less than 1%, even with a 90% hit rate probability, the result

probability will only be 8.3%. It will take many new evidence events to even increase the hypothesis probability

to greater than 50%.

If the result hypothesis is entered as the new base rate, and the other variables remain the same, one can get

an intuition of how the probability of the hypothesis becomes more certain given the mounting evidence. The base

rate must be as accurate, and relevant to the real life situation, as possible. If one doesn't know the hit

rate, or false alarm rate, estimates can be supplied for these variables.

More generally, Bayes's theorem is used in any calculation in which a "marginal" probability is calculated

(e.g., p(+), the probability of testing positive in the example) from likelihoods (e.g.,

p(+|s) and p(+|h), the probability of testing positive given being sick or healthy)

and prior probabilities p(s) and p(h): p(+)=p(+|s)p(s)+p(+|h)p(h). Such a

calculation is so general that almost every application of probability or statistics must invoke Bayes's theorem

at some point. In that sense Bayes's theorem is at the heart of everything from genetics to Google, from health

insurance to hedge funds. It is a central relationship for thinking concretely about uncertainty, and--given

quantitative data, which is sadly not always a given--for using mathematics as a tool for thinking clearly about

the world.

TL;DR

-

Tests are distinct from the event. We have a cancer test, separate from the event of actually having cancer. We have a test for spam, separate from the event of actually having a spam message.

-

Tests are flawed. Tests detect things that don’t exist (false positive), and miss things that do exist (false negative). People often use test results without adjusting for test errors.

-

False positives skew results. Suppose you are searching for something really rare (1 in a million). Even with a good test, it’s likely that a positive result is really a false positive on somebody in the 999,999.

-

People prefer natural numbers. Saying “100 in 10,000″ rather than “1%” helps people work through the numbers with fewer errors, especially with multiple percentages (“Of those 100, 80 will test positive” rather than “80% of the 1% will test positive”).

-

Even science is a test. At a philosophical level, scientific experiments are “potentially flawed tests” and need to be treated accordingly. There is a test for a chemical, or a phenomenon, and there is the event of the phenomenon itself. Our tests and measuring equipment have a rate of error to be accounted for.